Fenekere

Introductory text.

Contents

Fictional History

How does Maofrrao fit into our fictional mythology, and where did it come from? How does it work in practice?

Lexography

What does the writing system for Maorfrrao look like, and how does it work?

Root Words

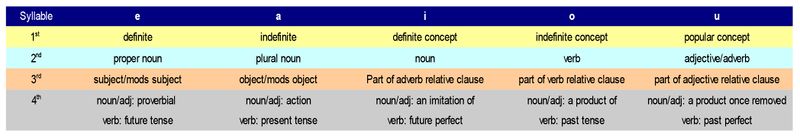

Root words in Fenekere consist of four consonantal phonemes and four vowels, making four syllables, with this structure: CvCvCvCv. The romanization appears to have consonantal clusters, such as CC and CCC, but in the original orthography these are represented by single characters. The default vowel, denoting the root meaning, for all four syllables is <e>. This renders the word to be a proper noun referring to an individual who performs a particular art or skill, an emotion, an element, a part of speech, or certain body parts that are considered elemental in nature.

All other primary words in Fenekere are derived from these roots by altering the vowel structure. As each syllable can contain one of five vowels, a table of these modifications looks like this:

As you make sense of this and read the following grammar, it is important to remember that nearly any combination of words and word particles is considered to be a legitimate sentence. But minor differences in placement of prefixes or vowels chosen for derived words can sometimes make enormous or very subtle changes in meaning. A listener may well be able to puzzle out what you mean, even if you get something slightly off, but until you get a feel for the subtle details it is always good and acceptable to double check.

Auxiliary Words

To accommodate a broader range of grammar structures and alter the purpose of a sentence, Fenekere has some auxiliary words. Most of them can stand alone in the sentence or clause and provide logical meaning to the whole structure. Many of them often serve time as prefixes as well, lending their meaning to the word that they are attached to (though this meaning alters in some ways, depending on which word they modify).

Particles

The three most important particles are 'uu, 'ii and 'oo.

'uu is the command or imperative particle. Placing it within a sentence transforms that sentence into an imperative or command. Depending on the structure of the sentence, this could translate into English as “May this happen...” or “You should do...” or in some other similar fashion. Note that it is entirely possible to create an past tense imperative sentence, though it is more common to use the pluperfect form of the verb in this case.

'ii is the interrogative particle. Placing it within a sentence turns that sentence into a question. If there are one or more pronouns within the sentence, the dominant pronoun becomes the focus of the interrogative voice. “This” or “that” becomes “what”, “they” becomes “who”, “here” becomes “where”, all without altering the morphology of that pronoun. It's meaning changes without it's structure changing (the particle takes care of that). The hierarchy of pronoun placement is as follows:

verb > subject > object > adverb > adjective of subject > adjective of object > adjective of adverb > adjective of adjective > object of adverb > verb of adverb > object of recursive verb.

Other ways of designating which pronoun is the subject of the question, that override this hierarchy, include stress or emphasis when speaking, underlining the word in written form, placing the pronoun at the beginning or end of the sentence, or placing the pronoun directly after the interrogative particle.

But, the most conventional method is to simply craft the sentence so that the pronoun of question is the soul noun in the subject clause. Most speakers and writers unconsciously employ two or more of these techniques.

'oo is the speculative particle. Placing this in a sentence is similar to adding “perhaps” to an English sentence. It means that the speaker is uncertain about the truth of the sentence. These particles can be mixed, with more than one per sentence. The hierarchy of the particles is as follows: speculative>imperative>interrogative. Meaning that if you included all three in a sentence, it would be similar to asking the English question, “Maybe you should do this?” Including just the imperative and interrogative particles, renders a question like, “Should you do this?” Etc.

Prefixes

Almost all of Fenekere's prefixes can work as stand alone particles. The way that they behave as such, however, varies from prefix to prefix. Most of the time, however, they are attached to a word and modify that word's relation to the rest of the sentence. These serve a whole variety of purposes.

For instance, in Fenekere, each verb has an implied preposition embedded within it that takes effect when an object is placed with the verb (they also have implied objects, if no object is provided). Some of these prefixes alter that prepositional meaning. And they may do so in different ways depending on if they are attached to the verb, the object, the subject, an adjective, or an adverb. A detailed description of how this works is provided below under the heading “Tricks with Prefixes: Prepositions, Moods, Voices and Aspects”.

Another way in which these prefixes alter words is by describing their relationship to other words of their position. If you have two objects, and you put the prefix for “greater” in front of one of them, then it describes that object as being larger than the other one. Finally, some prefixes will denote number, possession, or some other adjectival property applied to the word.

The way that each prefix interacts with the rest of a sentence is slightly unique to that prefix and is described in its definition.

Numbers

The numbers in Fenekere are based on the alphabet, which makes the system base 31. The consonants count from zero to 30, and the vowels are used to mark decimal placement. This covers whole numbers only, and has an upward limit of over 2 million, but with a definite upward limit. "e" represents the “ones” digit. "a" represents the 31s digit, and so on. To signify that a character is a number it is written backwards, or with the vowel first in the romanization, like so, "ef", meaning “one”.

To use a number in a sentence, however, it must be given some grammatical markers. In this way it is turned into a particle. This works similarly to the auxiliary words above, but with some slight differences. The typical method is to attach two syllables to the end of the number, each starting with a " ' " or glottal stop. The first appended syllable tells the part of speech that the number falls into. This is usually a "u", meaning it is an adjective or adverb. The second appended syllable tells the part of speech that it is modifying, like the third syllable does in a root word. So, to say that there is one of something, or that something happens once, you'd render it thusly:

ef'u'o or ef'u'a

If you want to say that something happens first, you would turn it into a prefix, like so:

ef'uu-

(insert numerical chart here)

Nouns

Fenekere root words are all proper nouns. From those proper nouns, a whole slew of other kinds of nouns can be derived. This effectively works the same way with every root word, regardless of the nature of its original meaning.

To identify any given word as a noun, the second syllable must contain an "e", an "a", or an "i". Given that, any of the other syllables may contain any combination of the other vowels, and this entire combination describes exactly what the noun means and where it falls into a sentence.

As described in the “Root Words” section above, the first syllable acts as sort of an article for the noun, telling whether it is definite, indefinite, or a variation of an idea or concept held by one or more people.

The third syllable defines which subclause the noun belongs to, whether it is the subject of the sentence, or the object of a verb of one of the subclauses.

The fourth syllable defines the relation of that noun to the meaning of the root word. The root word is generally considered to be an agent capable of performing a verb.

If a noun ends with an "e", it is an example of that agent.

If a noun ends with an "a", it is an example of the verb, a noun describing an action.

If a noun ends with an "i", it is an agent, but one that is an imitation of the root, such as an unskilled artist, an imposter, or something that just happens to be performing the verb but otherwise has another purpose.

If a noun ends with an "o", it refers to the product of the verb, such as a poem which is produced by the poet.

If a noun ends with a "u", it refers to the effect of the product of the verb, an effect once removed, such as the reactions of an audience upon reading or hearing a poem.

A novel example of the kind of noun you can create from a root might be “funimaru”, from the root “fenemere” meaning “the Poet”. Referring to the derivatives chart above, you can see that it means something like, “the commonly held stereotype of an audience's reaction to a poem” and it falls into the object position of a sentence.

Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjectives and adverbs in Fenekere all have a "u" in the second syllable. Otherwise, they work quite a bit like nouns. To work out the meaning of an adjective or adverb, figure out it's meaning as if it were a noun, and then apply the phrase “of or like” to the beginning of that. So, “funumaru” would be saying that the object of the sentence is “of or like the commonly held stereotype of an audience's reaction to a poem.”

You can tell the difference between an adjective and an adverb by the third syllable, which tells you which word it modifies. If it is an "e" or an "a", it modifies one of the nouns, and is therefore an adjective. If it is an "o", it modifies the primary verb. If it is an "i" it modifies the primary adverb.

And if it is a "u", it modifies the subject's adjective. All of these are technically considered adverbs. However, whether a word is an adverb or an adjective does not have bearing on its definition, only the word which it modifies.

The tricky aspect of Fenekere adjectives and adverbs is that they can either mean there is a similarity to the noun from which its derived, or it can be a possessive form of that noun. Normally, this is implied by a combination of the context of the sentence and the particular derivation of the noun. For example, “fenumere” would almost always be interpreted to mean “belonging to the poet” while “fenumera” would almost always be interpreted to mean “like or in the manner of composing a poem,” unless it's obvious from context that either word should be interpreted otherwise.

However, there are prefixes that can be used to clear this up when necessary. For instance, “firuu-” is the prefix for possession. It behaves differently when attached to a noun or a verb, but when attached to an adjective or adverb, it turns that adjective or adverb into an undeniable possessive noun. If attached to the primary adverb, this means that the verb is performed in the same exact method as the new possessive noun normally performs it, i.e. “in the way of -”.

Verbs

Fenekere verbs can be identified by an <o> in the second syllable, and they can fall into five different locations in a sentence as defined by the third syllable. Furthermore, each verb position can contain more than one verb, making it possible for an acting agent to perform more than one action. To compound this, the verbs do not have to share the same tense, though they will tend to share the same voice due to the context of the sentence's syntax.

Tenses

There are five tenses in Fenekere, governed by the five vowels like most everything else is, this time as placed in the last syllable. These tenses include: future, present future anterior, past, and pluperfect. Future anterior can be approximated in English with the phrase “will have been”. Pluperfect can be approximated with “has been”.

Because this last syllable is usually what tells us the relation a word has to the root, this means that verbs do not have this aspect. Instead, the verb is always assumed to be an act as defined by what the root word is capable of doing. “Fenemere” is “the Poet”, or “the Artist of Making Poetry”, therefore, the verb form “fenomere” means “to make poetry.”

Almost all Fenekere verbs contain within their meanings an implied object and an implied prepositional meaning. This can usually be worked out by understanding the meaning of the root word in combination with the context of the sentence. “The Artist of Making Poetry” will, when performing his verb, create “poetry”. And if an object is provided explicitly in the sentence, the nature of that object will suggest a prepositional relationship. If it's a person, then it can probably be assumed that the poem was made “for” that person. If it's a language, then it can probably be assumed that the poem was written “in” that language. And if it's a medium, it can probably be assumed that the poem was written “in” that medium. Prefixes applied to either the object or verb can be used to clarify this, or even explicitly use a different preposition altogether, such as “about” or “above”.

Transitive v.s. Intransitive

The flexibility of Fenekere verbs, with an optional implied object, means that any verb can be either transitive or intransitive. The interpretation of the verb relies entirely upon whether or not an explicit object is supplied in the sentence. And, regardless of word order, an object can always be identified by the vowel in its third syllable. Likewise, the subject.

If there are multiple verbs and one or more objects, all of the verbs are considered transitive and active upon the whole collection of objects. This is true even if the verbs do not share the same tense.

Passive Voice

Passive voice, in Fenekere, is achieved by simply leaving out the subject. In fact, you can have a full sentence simply by using one verb alone. For example, a sentence consisting of just the word “fenokero” would mean “poetry was composed”.

The exception to this is if the imperative particle 'uu is used. Then the sentence becomes a command, with an implied second person.

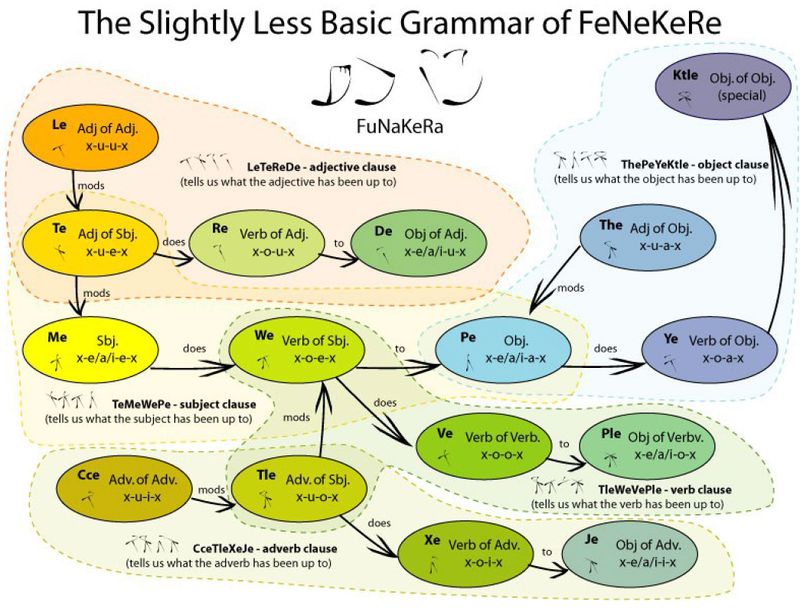

Subclauses

There are five possible complete subclauses in any given Fenekere sentence. These can be added to by using specific prefixes, but this gets clumsy and is usually avoided.

These five main subclauses revolve around the five verb positions, but are named after their respective subjects. There's the subclause of the subject, the subclause of the verb, the subclause of the adjective, the subclause of the adverb, and the subclause of the object. In each of these cases, the named word position acts as a subject of a clause that mimics the adjective-subject-verb-object structure of the main subclause of the subject. This can be visualized in the form of a word web.

Also worth noting is that connecting words do not need to be present to create a logical sentence. For instance, if you have the adjective of the object you don't actually need the object. This is particularly useful in a copula such as “fe bedodeha neku'ate” which means “I am happy”. It also means that some pretty strange sentences can be created, but the practice is to work out what that sentence most likely means rather than to declare that the sentence is gibberish.

Regarding the limited number of clauses that a sentence can contain, a complex recursive logic is

usually constructed by stringing together multiple sentences and linking them through a common pronoun referring to the subject or object of a focal sentence. When speaking, this can be further indicated by simple emphasis and stress. In written form, there are some punctuation that can aid in this as well. This is covered in detail below, in the section titled “Recursive Structure”.

Subclauses

Fenekere prefixes can be attached to any word. Also, there is no official upper limit to the number of prefixes that can be attached to a word, though in practice it is usually just one or two. This creates some subtleties of logic that can be manipulated by just how the prefixes are appended. The order in which prefixes are appended to a word, as well as just which word they are appended to can change how they effect the entire sentence. In this way, the meanings of specific words can be manipulated, prepositional phrases constructed, or moods, voices and aspects can be altered. This is similar to the way that English uses word order and auxiliary words to do the same kind of thing, except that the prefixes are typically attached to a word rather than placed alone in a sentence.

Below is a list of all of the prefixes and particles, and some examples of how they work:

• 'enaa – and/plus Unattached to any word, this particle connects the current sentence to the previous one: 'enaa firuubedodeha fe nenena - “And I am having that.” But, attach it to a noun, and it works like a conjunction within that noun's clause: fe firuubedodeha nenena 'enaanenena - “I have that and that.” Normally, it works the same way with any other word position as well, including verbs and adjectives. Normally, this is a little redundant, as the “and” conjunction is assumed in a list. However, it can occasionally clarify things. This particle is also used in mathematical equations for addition. • 'inee – except/minus This one works very much like 'enaa, except that it means “except” or “minus”. And when attached to a single word, it means that that word alone is an exception to the statement: fe firuubedodeha nenana 'ineenenena - “I have everything but that.” This particle is also used in mathematical equations for subtraction. • 'onuu - compounded by/times This particle is mostly used in mathematical equations for multiplication, though creative speakers and writers may also use it in prose to mean “complicated or compounded by”. It works in the same way as the previous particles above. • 'inoo - differentiated by/divided This particle is mostly used in mathematical equations for division, though it also is used by creative speakers and writers to mean “differentiated by”. In other words, it can be used on an adjective to describe the differentiating feature of a list of nouns: fe tegoremo nenana 'inoodeluna'a - “I ate those differentiated by how they were cooked.” If attached to a noun, it implies that noun is somehow between two things:

fe jenothena 'inoonenena - “I need that thing in the middle.” If attached to a verb or adverb, it adds a divisive property to the verb, meaning that the act itself divides or differentiates the objects: fe 'inootegorema - “I ate my food in portions.” • 'inuu - of This is the particle that can transform a noun or adjective into a true possessive noun. When there is nothing for that word to possess, or when this particle is attached to a verb, it acts as a preposition, clarifying the relationship of the object to the verb. It is not normally attached to the subject of a sentence, but you can do so if you think it will improve clarity in some way. It is never unattached to a word. • 'anuu - for This is another obligatory prefix that never appears unattached to the word. When attached to a word, any word, it designates that word as the reason for the argument, why the verb is performed. This particular prefix implies intention on the part of the agent, rather than a logical reason. • 'uuta – therefor This particle can be left floating in a sentence creates a logical connection to the previous sentence, just as with the English “therefor”. When attached to a word, it designates that word as the result of the argument. This does imply a logical relationship. • 'agaa – parenthetically/precidence This prefix is usually attached in conjunction with another mathematical prefix to indicate that the operation happens first. It can also be used in prose to mean similar things. It never appears alone. Usually it comes first, then the operator, then the stem word. • 'odoo – or This particle works exactly the same way as 'enaa, however it means “or” rather than “and”. • 'uuni - because of This particle works exactly like 'uuta, but designates the other part of the equation, the cause. • 'eele – if This particle works exactly like 'enaa, but designates the sentence or attached word as the condition upon which the argument depends. This is very flexible, and may mean that a single object among many may be the condition upon which the verb is performed. fe tegoreme nenena nenena 'eelenenena - “I will eat that and that, if I can also eat that.” • nimuu/e/a – yes/true In reply to a yes or no question, the shortest version of this particle, “nim”, is used as an affirmative. The variations “nime” and “nima” work as affirmative nouns in the subject or object positions as well: ne beodeha nima - “That is an affirmative.” When attached to a word as “nimuu-” it marks that word as true. This is particularly useful in conjunction with the conditional “'eele” and logical “'uuta”. 'eelenimuune 'uutanima - “if that is true then yes.” • noluu/e/a – no/false

This particle works the same way as nim-, except that it means “no” or “false”. It can also be used like “'inee” to mean “except”. It is very often used in front of a verb to indicate that the verb is not being performed. fe noluubedodeha gegega - “I am not you.” • ef'uu – once This is a particle based on the number word for “one”. You can actually derive similar prefixes from any of the numbers, in order to indicate “twice”, “thrice”, etc. The last vowel is used to indicate which word in a sentence that modifies. This works a little differently depending on which word you apply it to. fe 'efoktleta ed'uunenana - “I worked on two of those.” fe ed'uu'efoktleta nenena - “I worked twice on that.” ed'uufafa 'efoktleta nenena - “Two of us worked on that.” • ef'u'o/e/a/i/u - first This is a particle based on the number word for “one”. You can actually derive similar particles from any of the numbers, in order to indicate “second”, “third”, etc. The last vowel is used to indicate which word in a sentence that it modifies. ef'u'o fe tegoreo nenena - “first, I ate that” (before I did anything else) • bunu'o/e/a/i/u – last This particle works just like ef'u'o, but is not based on a number, and means “last”. • feruu/e/a – infinite This particle can work as either a prefix, “feruu-”, or as a simple noun in the subject or object clause, “fere” or “fera”. As a prefix, it means that the word it is attached to is modified by the concept of “infinite”. Although this is the literal meaning, and it used as such in mathematical and logical statements, it's very common to use this prefix metaphorically, as a way of emphasizing the worth or greatness of something. besheke'e bedodeha fera - “The Universe is infinite.” feruuuuuuuune - “That's cooooooooooool!” (literally “infinitely-that”) • buruu/e/a – finite This particle works exactly like “feruu”, except that it means “finite”. It is also used in slang to mean that something is less than impressive. • furuu/e/a – greater This particle works exactly like “feruu”, except that it means “greater”. This does mean that it can be used as a comparison or relation to other words in the argument. It is also used in slang to mean that something is excellent or good. • beruu/e/a – lesser This particle works exactly like “feruu”, except that it means “lesser”. This does mean that it can be used as a comparison or relation to other words in the argument. It is also used in slang to mean that something is generally inferior. • firuu – has This prefix may well be the most commonly used, so it is important to understand how it works. When attached to a noun, it actually indicates that noun is possessed by something else. Usually, it is applied to an object. It also works in a similar way with adjectives, indicating that the adjective describes a trait of its noun, rather than acting as a possessive noun itself. However, when attached to a verb, “firuu” gives the verb a possessive quality, allowing the subject of the verb to possess all of the objects of the verb.

fe firuunenena - “I have that.” fe firuubedodeha nenena - “I am having that.” fe firuutegoremo yefizamo - “I ate my breakfast.” fe tegoremo yefizamo firuuktlekibasho - “I ate the breakfast and my sausage.” fe tegoremo yefizamo firuuktlekubasho - “I ate the breakfast that had sausage.” • birruu – lacks This prefix works almost exactly like “firuu”, except that it conveys a meaning of loss, of “lacking”. But, it doesn't quite mean “minus” or “except”. It can have more to do with a sense of ownership than actual possession. This is a case where the change of one vowel can have a profound difference. fe birruunenena - “I don't have that.” fe birruubedodeha nenena - “I am not having that.” fe birruutegoremo yefizamo - “I ate the breakfast that wasn't mine.” fe tegoremo yefizamo birruuktlekibasho - “I ate the breakfast and the sausage that wasn't mine.” fe tegoremo yefizamo birruuktlekubasho - “I ate the breakfast that didn't have sausage.” • muzuu – however/but/despite This prefix means that the argument stands despite the word that it is attached to. It can also be placed alone in a sentence, unattached to a word, connecting the sentence to the previous sentence with this meaning of exception. muzuu fe firuunenena - “However, I have that.” fe firuubedodeha nenena muzuugegugo - “I am having that despite your influence.” fe firuubedodeha nenena muzuugeguga - “I am having that despite you owning it.” • biguu/e/a – weak When attached to a word, “biguu-” works like an adjective, describing that thing is weak in comparison to other words in the argument. When alone, it becomes a descriptive noun in either the subject or object clause, working almost like an adjective in some cases. But, unlike an adjective, it does not convey its meaning upon the other nouns in its clause, but either stands alone or passes that meaning through the verb to the subject. ke bedodeha biga - “They are weak.” ke tegorema biga - “They eat the weak.” ke biguutegorema - “They eat in a weak fashion.” biguuke biguutegorema biga - “They, who are weak, eat the weak, in a weak fashion.” • biruu/e/a – small This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “small”. • geruu/e/a – nearer This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “nearer” in relation to other objects in the clause. It also refers to space-time, rather than just space, or just time. It literally means “light will take less time to travel from there to here.” In practice, however, it means that you can use the word temporally as well as spacially. And, in fact, it is often used metaphorically when talking about concepts. • karuu/e/a - more distant This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “more distant” in relation to other objects in the clause. It also refers to space-time, rather than just space, or just time. It literally means “light will take more time to travel from there to here.” In practice, however, it means that you can use the word temporally as well as spacially. And, in fact, it is often used metaphorically when talking about concepts.

• girluu/e/a - in front of This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “in front of” in relation to other objects in the clause. • korluu/e/a – behind This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “behind” in relation to other objects in the clause. • farluu/e/a – above This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “above” in relation to other objects in the clause. • borluu/e/a – below This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “below” in relation to other objects in the clause. • ninaa – beside This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “beside” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • rlinaa – right/clockwise This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the right” or “clockwise” in relation to other objects in the clause. Although, the idea of “clockwise” isn't related to clocks in Fenekere. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • nirlaa – left/counter-clockwise

This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the left” or “counter- clockwise” in relation to other objects in the clause. Although, the idea of “clockwise”

isn't related to clocks in Fenekere. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • rlanii – northward This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the north” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • narlii – southward This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the south” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • kirraa – eastward This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the east” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • gerraa – westward This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “to the west” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • 'egoo – through This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “through” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • 'onaa – around This particle works similarly to “biguu-” except that it means “around” in relation to other objects in the clause. Also, it cannot be unattached to another word. • 'oonu – in This prefix is a bit reversed from the others. Placing it in front of a word means that the rest of the argument takes place “in” that word. Unless it is the verb, in which case the verb is taking place “in” the object.

• 'iiwo – only/just/merely This prefix denotes an exclusivity to the word it is attached to, that can also be taken metaphorically in certain contexts. • ccunuu/e/a – while This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “while” in relation to other objects in the clause. It also refers to space-time, rather than just space, or just time. It literally means “light from both events will arrive here at the same time.” In practice, however, it means that you can use the word temporally as well as spacially. And, in fact, it is often used metaphorically when talking about concepts. It is the closest concept to “in the same place” that Fenekere has. ccunuurre - “Right here and now.” fe fenokero ccunuutegoremo - “I spoke while I ate.” • cciruu/e/a – cause This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “this is a cause” in relation to other objects in the clause. There are some neat tricks you can do with “cciruu-” and the following prefix “ccaruu-” that can allow you to create complex logical structures in a Fenekere sentence. • ccaruu/e/a – effect This particle works exactly the same way as “biguu-” except that it means “this is a cause” in relation to other objects in the clause. There are some neat tricks you can do with “ccaruu-” and the previous prefix “cciruu-” that can allow you to create complex logical structures in a Fenekere sentence. • besheke - alien word When importing words into Fenekere, it is necessary to give them the vowels needed to fit them into the the grammar structure. The way this is done is to take the first three syllables of “besheke'e” meaning “the Outside” or “the Rest of the Universe” and appending them to the beginning of the word. Sometimes it is desirable to put the last syllable at the end. There are two modes of thinking regarding this, and neither is predominant among the speakers of the language, so it is left up to the individual to decide. One method is slightly more brief, easier to recognize, and pays somewhat less respect to foreign concepts. The other method allows for a greater flexibility in using foreign words, but is viewed by some to give them too much respect. besheke'u'esa - “U.S.A.” beshekeTomugacci'e - “Tamugachi” • geguu - yours • nenuu - its • kekuu - theirs • fefuu - mine • 'e'uu - Hers (the Earth's) • bebuu - His (the Father's) The above prefixes are examples of the possessive forms of various pronouns. They are always attached to a word, and denote that that word is belonging to the subject of the pronoun. This can be done with any of the pronouns, any of the Fenekere words that consist of one repeated consonant. You simply take the first two syllables, place an <e> in the first one and the double <uu> in the second, and append it to a word. When using

the pronouns that refer to the anatomy of a Fenekere sentence, they can be used to extend the structure of the sentence, as described below in “Recursive Structure”.